Introduction by Philip Harbottle

An Essay by Bertil Falk

Other Books by the same Author

Introducing The Original Golden Amazon by Philip Harbottle

One literary device that has been constantly employed by innumerable writers is that of the character series. And yet it is a device that has often been disparaged, particularly in the science fiction field. Robert Bloch, for instance, writing in The Journal of Science Fiction in 1953, made some sharp remarks, contending that: "…the fantasy and science fiction field is, in the main, guilty of standardization, stereotyping and formularising."

There is a good deal of truth in what Bloch wrote: series characters were frequently prompted by purely commercial exigencies, but was that necessarily surprising or reprehensible? Particularly in the context of sf pulp magazines? These magazines were commercial operations in a very competitive market place. Their editors were charged with pleasing their readers and thereby maintaining and increasing circulation. Purchasers of the magazine—the readers—merely wanted to be entertained. The latter-day criticisms of these magazines by the literati that they did not strive for originality and artistic excellence are completely spurious. Once a writer scored a popular success, more of the same became the order of the day.

Throughout the late 1930s and into the 1940s, all of the pulp science fiction magazines featured their own ‘series' characters (quite apart from the single character ‘hero' magazines such as Captain Future). They included, inter alia: Eando Binder (‘Adam Link'), and Nelson Bond (‘Lancelot Biggs') in Amazing Stories; Arthur K. Barnes and Henry Kuttner (‘Gerry Carlyle' and ‘Pete Manx'), Eando Binder (‘Anton York'), and John W. Campbell (‘Penton & Blake') in Thrilling Wonder Stories; Lewis Padgett (‘Gallegher') and Eric Frank Russell (‘Jay Score') in Astounding Stories.

In 1939 the typewriter of John Russell Fearn was doing a terrific business. He had increased his production steadily as new magazines appeared, writing under several pseudonyms, the most successful and popular being Thornton Ayre and Polton Cross. His most reliable and remunerative market was Amazing Stories, published by Ziff-Davis, and edited by Ray Palmer. In 1939 this magazine began paying a $50 bonus to the author of stories voted by readers as the best in a particular issue, and during the time it ran, Fearn regularly won the bonus under both these names.

When Fearn learned via his American agent Julius Schwartz that Palmer was buying material for a new companion magazine—Fantastic Adventures—and offering a $75 bonus, he had the brainwave of creating a new regular character for it—Violet Ray, otherwise known as ‘the Golden Amazon'.

His ‘origin' story, ‘The Golden Amazon' was enthusiastically accepted by Palmer, and appeared in the second (July 1939) issue of Fantastic Adventures as a 10,000 word novelette. Writing in the author's department of the magazine, Fearn frankly admitted that the character of the Amazon was ‘Tarzanesque' in origin—an infant lost in the jungle. But Violet Ray had been lost in the jungles of Venus, not Africa, a survivor of a crashed spaceship.

The baby had been found and brought up by Venusian natives. She had matured in the environment of Venus, where destructive cosmic rays were blocked by the dense atmosphere, but where solar radiation, due to the planet's proximity to the sun, seeped through. The outcome was steady anabolism, which transformed her into a woman utterly unlike any other. Instead of human cells breaking down, they had built up in ever increasing toughness.

Her intelligence had been enhanced to match her physique, enabling her to educate herself from books and tapes, which had remained inside the space ship that had crashed on Venus.

‘The Golden Amazon' describes how the girl had developed into a lone wolf, utterly ruthless and a law unto herself, dedicated to finding and smashing the criminal saboteurs who had caused the spaceship crash, killing her parents along with the rest of the crew. But she was still innately female and capable of falling in love…

Fearn revealed that he had been at pains to devise a framework whereby Violet Ray "…could step out of the ranks of the usual wise-cracking daredevil heroine and become something totally different…a new type of heroine with the brains of a genius and the strength of an Amazon."

The unique character of the Amazon afforded considerable novelty to the events, enabling Fearn to have fun with "a hero who is virtually at the mercy of the heroine… Usually these young men solve the most incredible things at lightning speed—a fact which has always struck me as unconvincing even though I am as big an offender as anybody!"

Fearn concluded his article on a prophetic note: "I believe that if this Earth born, Venusian bred girl interests the reader, there are no limits to which she cannot go. In a story such as this, definitely experimental, one cannot altogether encompass a wide range of story because of the necessity of stressing the character. Once the character is established the latitude for adventure is enormously increased. So, whether Violet Ray continues her exploits or not, getting into deeper water each time—for I have plenty lined up for her—depends entirely on you."

In the event, the story was an immediate hit with readers, who voted it into first place ahead of a novella by Edgar Rice Burroughs, thus winning for Fearn the $75 bonus, and opening the door for sequels.

There were three more Amazon adventures in the series, ‘The Amazon Fights Again' (June 1940), ‘The Golden Amazon Returns' (January 1941) and ‘Children of the Golden Amazon' (April 1943).

All of these stories were unashamed pulp. Spaceships are driven around the solar system like automobiles, and the action was fast and furious. Fearn was writing under the exigencies of difficult wartime conditions, and since during the early years of the war writing was his only source of income, Fearn had to tailor his stories to the requirements of the magazine editor. Ray Palmer had let it be known to his regular writers that in order to sell to him, stories had to be "simply told," and shorn of any "pretty, high-sounding phrasing." Authors were warned to blue pencil any phrases they considered to be ‘good' writing.

Towards the end of 1941, Fearn's situation changed. As the war continued and conscription was widened to include those people previously exempt (including writers and journalists) Fearn had been called up—only to be turned down by the armed forces on medical grounds.

But like everyone in wartime Britain, he had still been obliged to carry out ‘essential war work'. Eventually he had found an ‘approved' job in his home town of Blackpool—as a Cinema Projectionist, then a Reserved Occupation. His salary from this regular job meant that for the first time Fearn was not entirely dependent on his American writing income. After a decade of writing for the American pulps, he began to feel frustrated at its restrictions, and to consider upgrading his writing to break into other markets.

So that by the time the fourth Amazon novelette had appeared, Fearn had already decided to quit writing for the American pulp magazines, and those published by Ziff-Davis in particular.

His principal reason was financial: he had fallen out with his American agent, claiming he had not received recent (and substantial) monies due from sales to Amazing Stories and Fantastic Adventures. An appeal to Ziff-Davis and Palmer had fallen on deaf ears: they had paid the money to the agent, they said, and that was the end of the matter so far as they were concerned.

Always a mercurial and impulsive character, Fearn decided on a complete break from his agent and his established pulp markets. Although the money was eventually received, he broke with his agent and quit writing for the American magazines, deciding instead to make a serious attempt to establish himself as a novelist in his home country of England.

The rest, as they say, is history. Although only able to write part-time whilst he worked at the cinema, Fearn was extremely successful: within three years he was established in England as a prolific novelist, not only as a writer of science fiction, but also westerns and detective fiction. He even wrote two ‘mainstream' novels, Little Winter, and Then Came War, which he entrusted to a literary agency, but they were unable to find a publisher. Unfortunately both these mss have been lost and probably inadvertently destroyed.

Eventually, with the tide of war beginning to turn in Britain's favor, Fearn was allowed by the Authorities to resign his cinema job in 1944, and to resume his career as a full-time freelance writer.

However, throughout the war years, Fearn had pondered on the character of the Golden Amazon, and her vast potential. He had created her for Fantastic Adventures, but had resolved not to write for that market again. "The idea remained that she was too good to lose," he later recalled, "so I decided to make a full-length book about her…"

To do that, Fearn had to completely jettison all of the pulp elements in the stories, and indeed their entire plots. He upgraded his writing immensely in the process.

And at this point I beg leave to make an important point. For years, many bibliographers, so-called sf experts and critics, editors and reviewers, have all successively perpetuated a total myth about the Golden Amazon.

This myth is that Fearn "novelized" the stories from Fantastic Adventures for his first ‘Amazon' book, The Golden Amazon, in 1944. In point of fact, he did no such thing.

The myth seems to have taken hold because of a misleading statement in the landmark reference book The Encyclopaedia of Science Fiction (1993, and later revisions):

"Four Thornton Ayre novelettes in Fantastic Adventures featuring the superwoman—or Golden Amazon—Violet Ray were extensively revised into the novel The Golden Amazon (1939-43; 1944)."

This statement is simply wrong! But such is the status of this amazing reference

work (which successive critics and reviewers have unquestioningly accepted and

plundered) that this unfortunate misinformation continues to be perpetuated to

this day.

Even commentators well disposed towards Fearn contrive to

perpetuate the blunder. Anthologist Ann Hardin, for instance, in presenting her

Fearn selection (‘Martian Miniature') in Martianthology (2003), claimed that:

"Four of his ‘Golden Amazon' stories from Fantastic

Adventures were reassembled as novels, which were then reprinted in the Toronto

Star Weekly."

Here we see the seeds of a further ghastly extrapolation from

the Encyclopaedia's original error. That at least claimed that only the first

Amazon novel had been a fix-up, using an ‘extensive' revision of the four

stories. Now Ann Hardin appeared to suggest that no less than four book novels

were based on each of the short stories! God knows what the next commentator

will extrapolate from this weird variation.

Unless, that is, I can put a stop to this nonsense here and

now! Probably a forlorn hope, since I have many times already stated the true

facts in numerous articles, introductions, and even in a book published as far

back as 1968 (The Multi-Man.)

None of these commentators appear to have any real knowledge

of what they are talking about. It is quite obvious that they are perpetuating

the myth because they have not troubled to read the first Fantastic Adventures

stories of the Golden Amazon at all (nor even the later book novels, for that

matter.)

It seems to me that far too many science fiction book reviewers, instead of

confining themselves to an analysis of the book under review, feel compelled to

trot out additional "background information"—presumably to bolster their

credentials as critics. Such details appear to be an attempt to make the critic

appear knowledgeable about the field, and so add gravitas to their review. But

sometimes the writer does not actually have this background knowledge, and so

these de rigeur background details of the reviewer are simply filched from other

critics. Where the original source is erroneous, the later borrowing critic only

makes a complete fool of himself.

A recent blatant example is to be found in Rich Horton's

shoddy review of Dwellers in Darkness, the 20th Amazon novel. (The Internet

Review of Science Fiction, issue 4, 2004).

I have no quarrel with the condescending negative tone of the

actual review of the novel itself. Having read the novel, Horton is perfectly

entitled to his opinion, which is obviously genuine and as valid as anyone

else's. However, what I found objectionable in this review were the trimmings to

the actual review, i.e. the proverbial "background information" to establish the

reviewer's credentials.

Horton opens his review by confidently informing readers

that:

"John Russell Fearn was an English writer for the pulps—his best known pseudonyms were Volstead Gridban and Vargo Statten."

Anyone with any first-hand knowledge knows that there was no

such name as ‘Volstead' Gridban. The name was ‘Volsted'—there is, and never was,

any ‘a' in it. The Volsted Gridban name on books and stories only appeared in

England, so it is perhaps excusable that successive American commentators, who

have not seen the novels, persist in misspelling it. Perhaps they are

remembering the Volstead Act from the days of Prohibition in the USA?

Horton continues: "Beginning in 1939 in Fantastic Adventures

Fearn published stories in the Doc Smith mode but featuring a female anti-hero,

a man-hater, the Golden Amazon. These stories were fixed up into a novel in

1944."

This is utter and complete nonsense.

The first canard—concerning E.E. ‘Doc' Smith—probably stems

from the fact that, in my introduction to Dwellers in Darkness, I identified

some elements in that novel, which had clearly been borrowed from the stories of

Doc Smith. The existence of my introduction was something Horton's review

carefully contrived not to mention, though much of his further ‘background

information' about the Cosmic Crusaders was blatantly lifted from it. But at

least in lifting from me he got those facts right! However, as readers of my

introductions to the Amazon series will know, I had earlier identified the

"Smith mode" as only starting in the Amazon novels in 1948. The influence only

came in with the ninth novel, Triangle of Power, which Fearn had written

concurrently with his reading of the new book edition of Smith's The Skylark of

Space.

Fearn's much earlier stories in Fantastic Adventures were not

even remotely in the Doc Smith mode: absolutely no smidgeon of resemblance

whatsoever. Clearly, Horton had never read them, a fact obvious from his further

confident assertion that the magazine Amazon was "a man-hater." She was no such

thing!

The Fantastic Adventures Amazon was a completely normal heterosexual woman

(apart from super strength and her own ruthless ‘law-unto-herself' morality.)

The latter quality was caused because she had been brought up in the jungle, the

same as Tarzan. Fearn himself had openly declared her origin was Tarzanesque.

So much was the magazine Amazon not a man-hater that she quickly falls in love

with an ordinary Earthman, and promptly marries him. They even have two

children!

Finally, Horton—evidently an owner of a copy of The Science

Fiction Encyclopedia (the reviewer's friend!)—blandly informs us that the

magazine stories "were fixed up into a novel in 1944."

They were not: the novel was not a fix-up. It was completely original. And you

don't have to take my word for it, either. On the 4th January 1944 Fearn himself

wrote to his friend Walter Gillings:

"... To World's Work, I have sold The Golden Amazon — a

British version of the American Thornton Ayre shorts but with no possible

resemblance to them except maybe the title." This crystal-clear letter has been

reprinted several times, including the several book editions of Conquest of the

Amazon, but remains invisible to critics and reviewers.

The magazine Amazon operated some 120 years into the future,

with interplanetary travel an everyday thing. The 1944 book Amazon was set in

the present day, during the Second World War! Some ‘fix-up'! Some ‘revision'!

Fearn expanded on the further fundamental differences in a

later (1948) letter to Gillings:

"... In the original short stories she was lost on Venus as a baby, and the Venusian climate turned her into a superwoman: in the first novel about her, published by World's Work in April 1944 she was a baby lost in the blitz, operated upon by a super-surgeon. He changed her glandular structure, which—at maturity—would mean she would have superhuman strength, abnormally brilliant intelligence, and an almost sexless outlook on life."

But now that I have assembled these early magazine stories into a book, there

can be no excuse. Now readers and critics can finally see for themselves that

the two series are entirely separate.

Of course, trying to eliminate the misinformation concerning the Amazon's origin

is not the only—or even the main—reason for the appearance of this book now. In

recent years, several readers—and publishers—have written to me expressing a

desire to read these adventures of the prototype Amazon. Such is the rarity—and

cost!—of the original ‘collector's item' issues of Fantastic Adventures, that

they felt they would never be able to read them. And now that I have presented

all of Fearn's Golden Amazon novels, it seems inappropriate that the adventures

of the ‘other' Golden Amazon should remain in limbo. Especially as,

collectively, they made up a complete novel.

That they are not of the same high standard as the later

novels is unquestionable. They were written for an entirely different market.

More particularly, they were written to meet the requirements of editor Ray

Palmer, who insisted that stories were unashamed pulp adventure.

The stories were of variable quality. "The Golden Amazon,"

the ‘origin' story is quite a strong one, if one makes allowances for the

unlikely space travel elements, which simply transposed present day mariners and

sea vessels into space. The second story, "The Amazon Fights Again" is weaker in

sf terms, being mainly a transplanted gangster yarn, with space ships being used

as "getaway cars." It is a slam-bang action story, replete with all kinds of

melodramatic clichés. However, the story is not all it seems, because much of it

turns out to have been a spoof, and the clichés are deliberate plot devices. It

is further redeemed by a strong element of humour, as Chris Wilson, now the

Amazon's husband, and a quite ordinary man, flounders around in the Venusian

environment in the wake of his indomitable wife.

The third story, "The Golden Amazon Returns" is by far the

best, since it is genuinely inventive and science fictional. Its quality was

recognized by Michel Parry, a leading anthologist, when he included it in his

collection Superheroes. Fearn's story appeared in both of the two separate

versions of the book in 1978 and 1984. I myself borrowed its very strong central

sf premise of a solar lens in the Moon for my own first Garth comic strip

adventure, "Twin Souls" serialized in the Daily Mirror newspaper in 1993.

The final novelette, ‘Children of the Golden Amazon' takes

place some eighteen years on from the previous story, with the Amazon now a

widow and her two children grown up, having inherited her super-strength. The

most fantastic story in the series, it had probably been held in the magazine's

inventory for some time before publication. It showed distinct signs of

editorial interference by editor Ray Palmer, who appears to have tweaked the

story to match the cover illustration by Malcom Smith, and more deleteriously to

try and fit a vivid black and white interior illustration by Frank R. Paul, that

departed considerably from Fearn's original story.

Paul depicted two separate Mercutian races, the dominant one

a kind of butterfly, and a servitor race of giant grasshoppers! Fearn's story

involved a single race of Mercutians, who are an energy-based life form, and

neither butterflies nor grasshoppers! They had no real connection with Paul's

illustration. But Palmer's tweaking fell well short of doctoring the text

sufficiently to match the illustration completely. His changes were mainly

limited to the giant grasshoppers, and were quite incongruous. I have therefore

restored an approximation of what I believe would have been Fearn's original

Mercutians.

Summing up, Fearn had created a memorable central character

in the Golden Amazon, who deserved a better stage than Palmer's Fantastic

Adventures, where the market restrictions meant that the Amazon could not

entirely transcend her pulp trappings.

And that is why Fearn started all over again, jettisoning all

of her pulp background, and upgrading his writing for the U.K. hardcover book

market. The World's Work and Toronto Star Weekly Amazon is therefore a

completely separate character, and not a fix-up version of the original stories.

Despite its shortcomings, the original Amazon series was of

undeniable historical importance, not least because it began more than two years

before the publication of ‘Wonder Woman', science fiction's more acclaimed

super-heroine, who debuted in DC's All-Star Comics for December 1941!

Wonder-Woman Diana Prince was also an Amazon who, with her super strength and

intelligence, routed criminals and villains.

During the war, many of Fearn's stories from the American sf pulps were

translated into Swedish and published in the Jules Verne Magasinet (later

Veckans Aventyr). These reprints included all four Golden Amazon novelettes. The

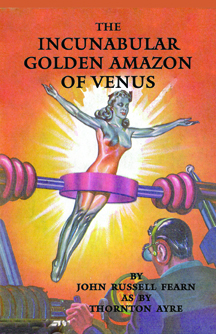

character was popular with Swedish readers, and was featured on three covers: in

her original appearances, only the last story had made it to the cover of

Fantastic Adventures. This vivid cover was the work of the talented artist

Malcolm Smith, and was also copied on the Swedish version. It was therefore the

natural choice to form the basis of this present book's cover. All four story

reprints are listed in my Amazon bibliography elsewhere in this book, and are

more particularly discussed in their Swedish context in a wonderfully

illuminating article by Bertil Falk, specially written for this present volume.

And so, here collected together to form a novel, are Fearn's

stories of the ‘original' Amazon— The Golden Amazon of Venus. Also included in

this volume as an appendix is a world-wide bibliography of all of the Golden

Amazon stories and novels—all of which are currently in print, testament to the

fact that the Golden Amazon is Fearn's most enduring creation.

— Philip Harbottle

Wallsend,

November, 2006